Seed valuations don't behave like valuations:

They are too stable over time for such a speculative asset

They are impervious to shifting interest rates

They don’t follow public tech valuations

In short, seed valuations are a bit of an enigma — it’s not at all obvious what drives them. However investors arrive at these numbers, they aren’t doing so based on typical Finance 101 factors like discount rates or comparable company analysis.

Seed companies don’t seem to be priced as businesses with intrinsic value derived from future cash flows. Rather than venture capital, they seem to be a proxy for the human capital of the founders and early team.

Seed valuations aren’t valuations.

Non-standard deviations

First: seed valuations aren’t volatile enough.

This really stood out when constructing my Venture Activity Index – the volatility of the late stage is much higher than the early stage, which is true even if you exclude the pandemic era:

This is strange. If seed stage investments are as speculative as they’re purported to be, we'd expect wild valuation fluctuations over time. Late-stage valuations should be more stable, since they have an existing business model, revenues, and potentially even cash flows (hard to believe, I know).

Imagine if large, blue chip stocks were more volatile than small caps. That wouldn't make much sense. The stability of seed valuations relative to more mature startups makes no sense either.

As I’ve previously covered, capital flows affect valuations, and this force is most extreme at the later stages where the so-called "crossover funds" (funds who've crossed over from public market to private market investing) are most active. Thus, capital flows drive excess volatility at the later stages. However, I don't think that can explain everything going on here.

And yes, there are many more seed deals getting done each quarter than later-stage rounds, so due to some fundamental laws of statistics we’d expect less variability with a larger sample. Even so, seed valuations seem too stable on a relative basis.

Discount rates don’t matter if there’s nothing to discount

Second: interest rates don’t affect seed valuations.

In the standard corporate finance logic, early stage companies should be the most sensitive to interest rates because they have the highest duration. Think of duration as a measure of distance, measured in years, to the average dollar of cash flow for a business. For early stage companies, all cash flow the business will ever produce is far into the future, so they definitionally have high duration. In a discounted cash flow model, seed valuations would be extremely sensitive to movements in the discount rate, similar to a long-dated bond:

Duration measures the sensitivity of the value of a bond to a change in interest rates, which is tied to the lifetime of the bond. Bonds with longer tenure or back-loaded cash flows are more sensitive to changes in interest rates

Due to the multiplicative nature of discounting, the present value of far-away payments is more sensitive to a change in interest rates than the value of soon-to-come payments – High Retention = High Volatility

That's not what we see. Some time ago I investigated the “average” impact of interest rate surprises on venture valuations across all stages. I've since revisited and refined that analysis, adding more granularity to the estimates. I've also stripped out the COVID era, where the impact of fund flows contaminates the estimates.

What I found was fascinating. Here's the impact of a surprise 1% increase in the one-year Treasury yield across seed, Series A / B, and Series C / D, along with a measure of uncertainty around these estimates, going twelve quarters out:

Interest rates have no effect on seed valuations. Not only is the impact zero, it’s precisely zero. There isn't a ton of uncertainty around these estimates.

For Series A / B, we start to see some effect, maxing out at a 16% decline seven quarters after impact before recovering.

For proper growth stage rounds like Series C / D, the impact is even quicker and more severe, peaking at 19% six quarters out.

This is the most striking evidence — the clearest indication that investors value seed stage startups in a totally distinct way to the rest of the venture market. It’s hard to rationalize this evidence within the usual frameworks.

They not like us

Third: public tech valuations don’t influence seed valuations.

When the big tech (“FANG”, the “Magnificent 7, etc) valuations move around, private valuations typically follow, with a lag. This makes intuitive sense given venture investors use comparable public company valuations to decide how much they’re willing to pay for private companies. In a rational market we’d expect some correlation between public and private valuations, even if imperfect. This is “comps analysis” in a nutshell.

And that’s what we see — except for seed companies:

When the Nasdaq rises 1%:

Series A through D valuations rise, matching the bump in the Nasdaq within about a year.

Seed valuations don’t move at all, marching to the beat of their own, relatively quiet drummer

While there’s a very clear pass-through effect of public prices on private valuations for most stages, seed startups are the exception, seeing no pass-through at all. It turns out, investors don’t care about public comps when pricing seed stage companies.

It’s clear that seed valuations are not really valuations in the traditional sense. They don't behave like valuations in either their volatility over time or their sensitivity to interest rates. Something else must be going on here.

These prices are sticky too

It struck me that seed valuations were incredibly sticky (an early working title for this essay was "Why are Seed Valuations so Sticky?”). Seed valuations neither rise nor fall dramatically far from trend, whereas other stages see much strong gyrations:

This "stickiness" is unique to seed valuations and doesn't mirror the behavior of free-floating financial assets, which are typically much more volatile and difficult to forecast.

I stared at the seed valuation data for a long time as I contemplated this essay. As my eyes glazed over, I tried to come up with analogues, other phenomena that mimic the behavior of seed valuations.

Then it hit me – wages. Wages are often said to be “sticky”, and seed stage valuations look eerily similar to wages over time, which also tend to be quite stable around a long-term, upward trend.

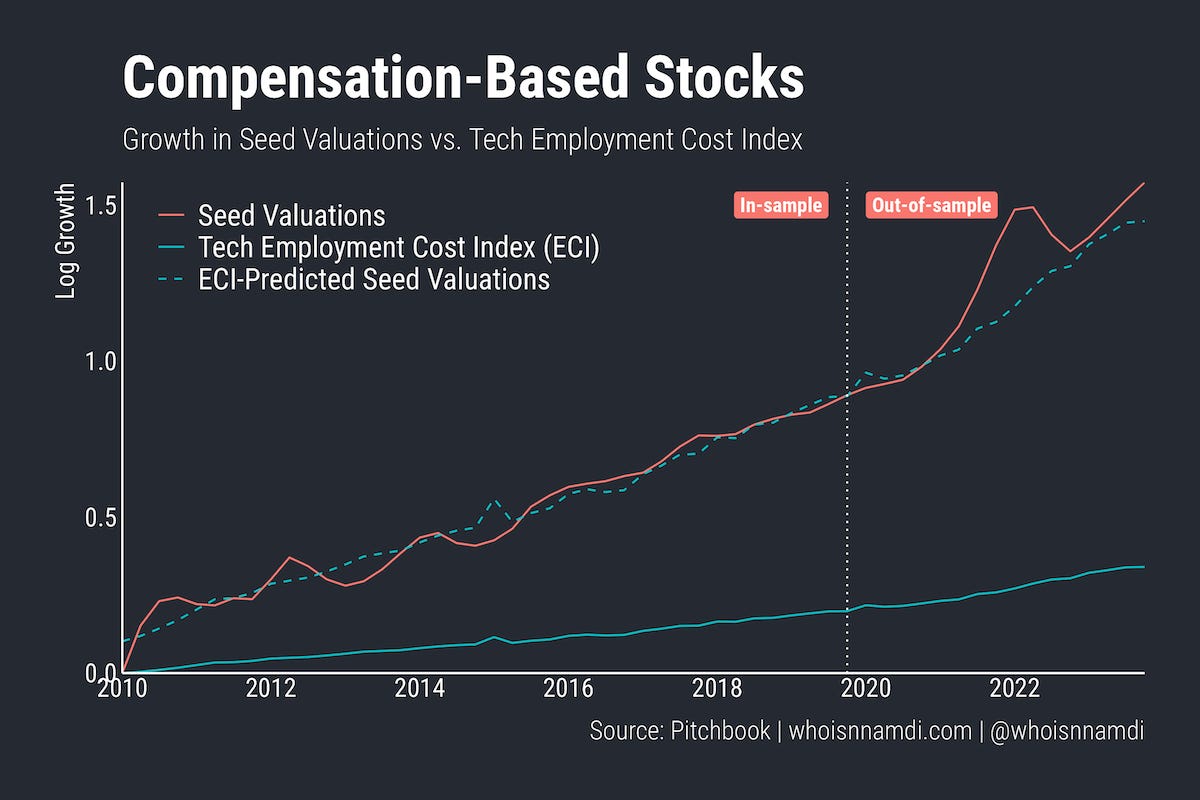

The simplest thing to do is plot compensation against seed stage valuations. I found a wage series called the “Employment Cost Index” (ECI) that measures compensation growth over time, and I pulled out a version of this that’s specific to “professional, scientific, and technical services,” which I take to be a good proxy for tech workers:

The first thing that stands out is the obvious difference in growth rates. Seed stage valuations have risen much faster than wages for the typical tech worker. For every 1% increase in tech worker wages, seed stage valuations grow 4-5%.

We can predict seed stage valuations from the wage data. I regress seed valuations on the ECI using pre-2020 data. The fit is tight pre-2020 (which is frankly easy since they’re both roughly straight lines).

Then I evaluate its forecasts on post-2020 data, “out of sample”. The model returns to a reasonably close fit once valuations settle down after the 2021-2022 bonanza.

Notably, seed valuations bottomed out at exactly the level you would have predicted using the employment cost index.

This feels like more than coincidence. Regressions do have a high risk of being spurious, which is to say, total nonsense. I was skeptical the first time I ran these numbers. But after multiple sanity checks, this seems to be the real deal. There is a tight connection between seed valuations and wages for tech workers; the two follow the same trend, one an accelerated version of the other. Thus we have a scaling law between tech wages and seed valuations:

The inverse of stock-based compensation, seed companies appear to be compensation-based stocks, at least in how they’re valued.

Google is my BATNA

This analysis doesn't prove anything, but it does suggest an interesting link between tech wages and seed valuations.

Why would seed valuations be linked to the cost of tech labor? And why would those valuations grow so much faster than wages? I’m not even 100% convinced that it’s a direct, causal connection — perhaps there’s some third variable that drives both. Totally plausible. I plan to explore this in a future piece.

Regardless, it’s quite clear to me after crunching the numbers that seed valuations don’t behave anything like valuations, at least not valuations of companies or speculative assets. Their stability suggests investors have a precise sense of their worth, despite their riskiness. The value investors place on these companies does not fluctuate wildly over time.

This is odd only if your mental model values these fledging enterprises as… enterprises. What if seed stage valuations instead represent the value of the labor and human capital of founders and early employees? The behavior of seed valuations would make a lot more sense if we saw them as proxies for the opportunity cost of talented tech workers.

I’ll explore this hypothesis in a future essay.

Originally published on whoisnnamdi.com

This is hands down the best quant analysis of seed validations I’ve ever read. Thanks for the work on this, will be giving you a shoutout in my next newsletter.

Perhaps seed valuations should be more seen in the light of option valuations. Basically an investment in the seed stage is buying yourself an option for future cashflow. The key drivers for the option are the volatility, interest rate and time of the option. I guess the runway funding it the option period of the company. It is indeed interesting how interest rate therefore doesn't influence the pricing as it would do on an option. Interesting to get corporate finance theory view on this.